Gary Giddins, jazz scholar and cinema scribe, puts to work his sharp antennae and vigorous pen in Warning Shadows, a collection of film reviews in which he cheers and challenges established and forgotten classics, as well as the obscure, the arty, and the awful.

Like Orion, Gary Giddins is a hunter of shadows. Time and again, he’s drawn to those overcast aesthetic zones where the best alchemic prizes can be found, fondled, and fathomed. An admired critic with a remarkable body of work, his fondest preoccupations are jazz, that supremely shadowy realm of music, and movies, an art form that blooms most beautifully in the dark.

The legendary Louis Armstrong is the subject of Gary Giddins’ Sachmo, described by The Nation as “the best appreciation of a musician whose genius as a trumpeter, improviser, singer, and entertainer still defies comparison.” [1]

A native New Yorker, Giddins has been most prolific in his written investigation of jazz, a fascination that’s kept him perceptively busy for decades. From 1974 to 2003, he wrote the jazz column Weather Bird for The Village Voice, and has authored eight highly-regarded books devoted to the topic. Among them are studies of Charlie Parker (Celebrating Bird, 1986) and Louis Armstrong (Satchmo, 1988); the monumental 700-plus pages of Visions of Jazz: The First Century (1998), winner of the National Book Critics’ Circle Award, and hailed as a “the finest unconventional history of jazz ever written” [2]; and Bing Crosby: A Pocketful of Dreams (2001), a “must-read” [3] exploration of the singer’s musical legacy, which includes a significant authority in jazz technique. (Two of Giddins’ eleven publications, the 1996 Faces in the Crowd and the 2006 Natural Selection, can’t be described as solely jazz books since they explore other regions of the arts–films, literature, comic books–as well as a selection of their outstanding creative representatives.)

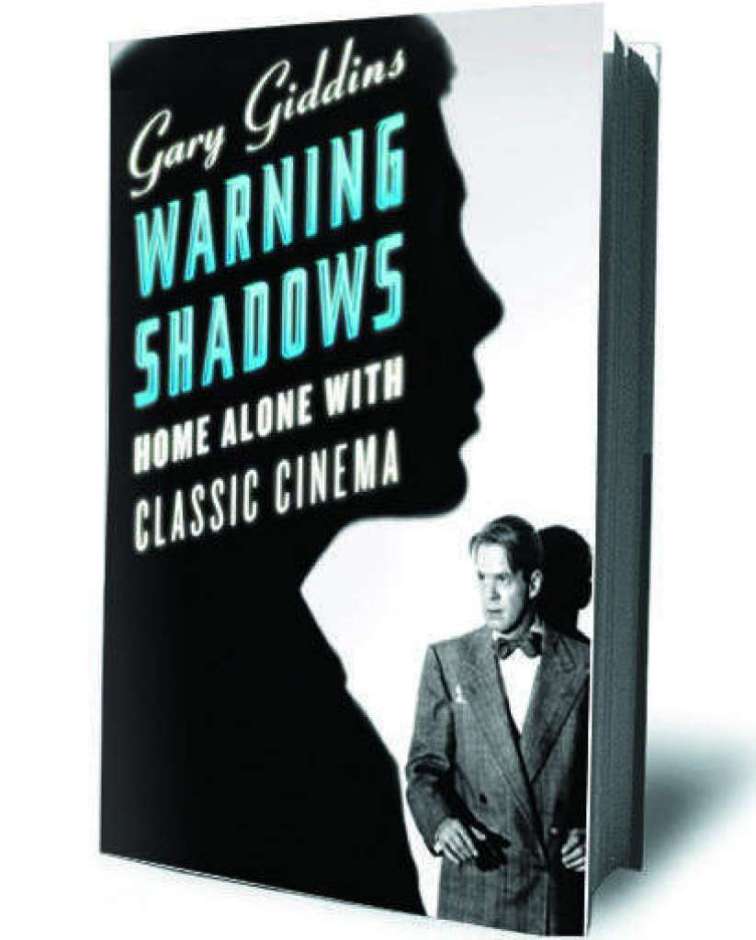

And on the subject of movies? Giddins’ output is less voluminous–only one of his books deals exclusively with matters cinematic, the 2010 Warning Shadows: Home Alone With Classic Cinema. But Giddins the movie scribe delves into film culture with such adept enjoyment that he all but promises to one day catch up with his musical self. Written with tireless flair and commitment, Warning Shadows has kept me gladly engaged of late and hoping there’s another of its kind in the works.

Chicago’s Uptown Theatre, which opened in 1925 and closed in 1981, was described with only partial hyperbole as “an acre of seats in a magic city.”

Covering countless vintage productions released on DVD and Blu-ray, Warning Shadows is a compilation of reviews and profiles, most of which originated in The New York Sun, a daily broadsheet published from 2002 to 2009. Others found their place of introduction in DGA Quarterly, The New York Times Book Review, Film Comment, and The Criterion Collection. Commencing on a historical slant, Warning Shadows whisks us into a fifteen-page examination of how we’ve watched movies since their very beginning, focusing on each cycle’s ways and means of exhibiting filmed works. Thomas Edison’s rudimentary but revolutionary kinetoscope (a peephole machine which allowed a single viewer to watch “moving pictures, fluid as life”) gives way to a sweeping industrial shift toward theatres (with the popular storefront nickelodeons rapidly superseded by the early rococo picture palaces sporting domed ceilings and lobbies brightened by chandeliers). The current dominant practice of home viewing concludes the saga as television, videotape, laserdisc, and DVD and Blu-ray get their moments of mass production and cultural influence. Approaching moviegoing in environmental terms, Giddins touches on the impact and distinction of various forms of motion picture display, our responsiveness from format to format, the resulting changes in how movies were made, the technological innovations, our expectations according to different mediums, and the alterations in our habits of consumption. Yet for all the art, science, and commerce that have shaped films, the most immersive approach was discovered early on when celluloid shows were unveiled for crowds of eager onlookers. “DVD and Blu-ray,” Giddins states of the current phase, “are substitutes for the intended experience.” The collective response, I agree, is the most emotive and memorable, and watching movies, no matter what the era or its controlling presentational modality, is ultimately a tribal sport.

The Tales of Hoffman, a sumptuous adaptation by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger of Jacques Offenbach’s opéra fantastique, which was first staged in 1881.

Movies, like jazz, set Giddins alight as a writer, and Warning Shadows is an energizing read, divertingly pacey and alive with word sense and pictorial memory. Blending a scholarly informality with an addict’s allegiance, Giddins can isolate filmed sequences, moments, and qualities with a deftness that accelerates one’s remembrance of them. He launches the hues, textures, and design of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s The Tales of Hoffman (1951) into our quickened recollection when he states that “the décor and the actors are drunk with colour.” In that potent bit of tribute he captures the fullness of the images, the riskiness of their abundance, and the almost intoxicating gracefulness of the dancers. Giddins has sharp antennae and a vigorous pen, and his writing can be winningly descriptive: his encapsulation of actor Simon Russell Beale’s unpleasing mug in the 1997 British mini-series Dance to the Music of Time conveys a contemporary Dickensian prickle, and his appreciation of cinematographer Edward Cronjager’s lustrous lighting in H. Bruce Humberstone’s I Wake Up Screaming (1941) may very well prompt you to check it out.

Murder suspect Victor Mature becomes enmeshed by the expressionistic lighting of cinematographer Edward Conjager in the 1941 I Wake Up Screaming.

A true believer as well as a permissive fan, Giddins sometimes indulges movies almost as much as he honours them, and their fealty to the formulaic and the unending volume of happy endings that they offer can, under the right circumstances, be as pleasing to him as the stylistic surprises and emotional ambiguities found in films of a higher order. Of Peter Watkins’ ambitious structural technique in Edvard Munch (1976) he approvingly writes: “These are not explanatory flashbacks of the kind running amok in recent biopics. They are integrated glimpses of the past woven into a narrative mosaic, and they have the effect of flattening perspective, as Munch did on canvas.” But: commenting on Sophia Loren’s luxuriant appearance while languishing in a medieval prison in Anthony Mann’s El Cid (1961), Giddins notes: “Clearly jailors have been smuggling in lipstick, rouge, mascara, and other concealers, and who would want it any other way?”

Orson Welles’ 1955 thriller Mr. Arkadin endured many mishaps of production, editing, and distribution, resulting in the director’s most wayward film. Cast as the romantic leads are Robert Arden and Paola Mori—Welles’ third wife, whose vocals were dubbed by Billie Whitelaw.

Warning Shadows covers a good deal of turf, zeroing in on the best and the brightest as well as the odd, the esoteric, and the awful. Influential classics get their due praise, seasoned with filmic associations, background data, and memorable summings up. Giddins surprises with an unexpected visual link between the Korda mounting of The Thief of Bagdad (1940) and Hitchcock’s North by Northwest (1959), and he tweaks one’s curiosity with the statement that Orson Welles was never more charismatic than as the mystery figure of Carol Reed’s The Third Man (1949), not even in one of his own films. (What was Welles unable to find in himself that Reed perceived, empowered, and snared for his own purposes?) Giddins’ enthusiasm for buried beauties and neglected orphans has him finding noteworthy viewing in drive-in fare and grindhouse leavings. He bids welcome to Curtis Harrington’s macabre resurrection of Ann Sothern and Ruth Roman in the little-seen The Killing Kind (1973), tips his hat with a slight tremble to the crawly Spanish curio Who Can Kill a Child? (1976), and allows an amused, tolerant nod for a series of silent films starring Harry Houdini, the King Kong of escape artists. A new cut from Criterion of Orson Welles’ troubled Mr. Arkadin (1955), haunted for decades by its many multiplying versions and the attendant inconsistencies and convolutions, is, like all previous prints, “mangled, contentious, and undying.” But this latest release nevertheless makes a case for itself as “a genuine Wellesian achievement.” He also covers some Absolute Essentials of long ago: his entry on Buster Keaton’s The General (1926) charmingly evokes the film’s beautiful sense of movement, timing, surprise, and the director-star’s creative ownership of the material. Even if you’ve habitually seen whatever film is under discussion, Giddins is likely to make it seem fresh again, which is almost like making it new.

Sabu, in the title role of the Kordas’ Thief of Bagdad, keeps his aim true while positioning both his crossbow and his performance.

Which isn’t to say that he’s without the occasional missteps. He sometimes makes his case by overstatement, like so: “No one knew more than the spellbinding Edward G. Robinson about how to hold and control a scene.” It may seem that way when watching him, and there’s no denying Robinson’s power and distinction. But there have been plenty of actors who could go fifteen minutes in the thespic ring with Edward G. and match him, or even, in certain respects, knock him cold. (The list of contenders is probably too long and varied to bother with here, though Brando and Bogart leap promptly to mind.) But in such moments Giddins errs on the side of enthusiasm and aesthetic loyalty–not such a disgraceful guilt if you possess the critical skills to match your dedication. Fortunately, he does, and with much to spare. His wit and insight are as evident as his amazement at the power of films and his delight in understanding them. Gary Giddins is a bracing reminder that being overwhelmed by movies is irresistible, but figuring them out is sometimes the best fun of all.

Articles

[1] “Not Even Bing’s: On Louis Armstrong,” David Schiff, The Nation, February 11, 2010

[2] “All That You-Know-What,” Alfred Appel, Jr., The New York Times, October 18, 1998

[3] “Bing Crosby: A Pocketful of Dreams, The Early Years 1903-1940 by Gary Giddins” Bill Milkowski, Jazz Times, January 05, 2001